Interview with Chef Sean Brock – Charleston, SC and a recipe for Hoppin’ John

How many different varieties of rice can you think of? How about different peas? If you are like most people you will probably be able to name a dozen types of rice and maybe half a dozen types of peas. Would you be surprised to learn that there are over 100,000 varieties of rice, of which 40,000 are cultivated varieties and that Thomas Jefferson cultivated over 20 varieties of peas at Monticello?

So, why is it that when we go to the grocery we typically find such a small selection of produce and meats when there could be more? The answer is simple. Our food supply has been dumbed down to the few varieties that are cheap to produce, easy to transport and have the longest shelf life. As a result, our culinary tastes have also been dumbed down and the dishes that we ate just 100 years ago do not have the same taste today because we have substituted inferior varieties of produce and other ingredients.

We went On the Road in April to one of our favorite cities, Charleston, South Carolina, to speak with a chef that is committed to bringing back our heritage foods with their rich and unique flavors. Every visit to Charleston is filled with fabulous food, great chefs and inspiring stories. This time was no exception and perhaps, our most memorable.

Chef Sean Brock, of McCrady’s and Husk fame in Charleston, is also the recipient of the 2010 James Beard Best Chef Southeast award. In addition to other awards, numerous articles in magazines and newspapers, television appearances and participating in events like Atlanta Food and Wine, Chef Brock is writing a book. He is incredibly busy, to say the least.

Main Dining Room at McCrady’s

Born and raised in the South, Brock is proud of his heritage and Southern food. He was raised on a farm and spent days as a boy shucking corn or shelling peas. Some say that he is the best farmer to ever become a chef. Passionate describes every chef and farmer that we have met since we started our travels, but Brock may be taking that word to a new level in his mission to fix what has been broken in the way our foods are grown and raised.

The bar at McCrady’s

Brock, a graduate of Johnson and Wales, initially came to Charleston for culinary school in 1997. He began his career at Peninsula Grill in Charleston. After working in several other restaurants in other cities (The Hermitage Hotel in Nashville, Tennessee, Lemaire in Richmond, Virginia, and La Terraza del Casino in Madrid), Brock came back to Charleston five years ago as Executive Chef at McCrady’s. It was this transition that was a life changing experience for him.

Once known as McCrady’s Tavern (originally owned by Edward McCrady), this historic building dates back to 1788. It was a local tavern along with a brothel upstairs (at one point) during its history. Back in those days, the building was located right on the waterfront, but over time the land was filled in and now sets back several blocks from the shoreline. There have been many notable patrons of this tavern over its long and colorful history, including George Washington in 1791.

This wall is part of the original exterior of McCrady’s Tavern

It was the historical significance of this building and telling the story about that history that has had the greatest influence on this chef over the last five years. He started to think about the foods that were served in McCrady’s Tavern hundreds of years ago and set out to find the original species of plants that once existed in the region to bring back the true flavor profiles that Charleston is known for.

Dishes that were indigenous to the area like Shrimp and Grits, She Crab Soup, Hoppin’ John and Oyster Benne Stew now tasted nothing like they did. Local rices, produce and beans used in these dishes disappeared in the 1930‘s. Over time, genetically engineered rices, dried beans and seafood from cheaper sources took their place. Brock felt a responsibility as a chef to do something about it. Inspired by others, he started to grow heirloom varieties of plants that belonged in Charleston’s kitchens on his own farm. He sourced other heritage products, such as meats and poultry, to bring back the flavors that Charleston enjoyed hundreds of years ago.

Upstairs at McCrady’s

When Brock came to Charleston in 1997 to attend Johnson and Wales, he was excited to be in the same city with great chefs like Louis Osteen, Robert Carter and Bob Wagonner. He studied the cuisine of Charleston. One of the dishes that left him unimpressed was Hoppin’ John. It tasted like cardboard and he couldn’t understand what the excitement was over this dish. What could possibly be good about Uncle Ben’s white rice and black eyed peas that were stale and dry?

The problem was that it wasn’t the authentic dish. It was missing the historical link to the proper ingredients for the dish: Carolina Gold Rice and Sea Island Red Peas. Every chef in the city should have been serving the original version, but they weren’t because the ingredients were no longer available and they substituted easily available ingredients.

Brock refers to the Hoppin’ John theory as a perfect representation of our current food situation. To paraphrase Chef Brock, certain traditional dishes are still demanded although they are not authentic. When you start with poor ingredients and there is little passion in preparing the food, you end up with a bad representation of what the dish should be. This is why we must go back to the original ingredients and recreate these flavor profiles.

The chefs at McCrady’s have beautiful local produce to work with

All of the ingredients were gorgeous

Rice came to Charleston by accident in 1681. A storm blew a damaged ship from Africa into port and the repairs for the ship were paid for in rice seed. Two farmers planted the seed and found that it grew quite well in Charleston since the climate was similar to that of Western Africa. This rice became known as Carolina Gold Rice.

Lardo that has been aging in Pappy Van Winkle casks

Golden fields of rice, hundreds of miles long, were once visible along the coastline of South Carolina and Georgia. In fact, at one time there were over 100 varieties of rice grown in this area. Rice was one of the reasons there was so much wealth in Charleston. However, that all changed when the last of the Carolina Gold Rice was harvested in the late 1920’s due to overproduction, collapse of the market, lack of available laborers and to make way for crop rotation to improve the soil.

The workers (slaves) that were brought from Africa in the 1700’s and 1800’s had a vast knowledge of agriculture and crop rotation and used the Cowpea (brought over from Africa) as an essential source of nitrogen for the soil. They were growing these peas, but they were mostly used for animal feed or fertilizer and for many years never made it to the main house as food. (The main house was known as The Big House to the slaves.)

Chef Brock prepared ramps for us at McCrady’s

I can understand why they are one of his favorite things to eat

At some point along the way, the Cowpea (or Sea Island Red Pea, as it is known in South Carolina), finally made its way into the kitchens of the main house and someone tasted the combination of Carolina Gold Rice and the Red Pea and Hoppin’ John was born. (That is one of the theories for the origin of the dish.) . Unfortunately, as these ingredients disappeared over time, the authenticity of the dish was lost and white rice and black eyed peas were substituted in the dish. That combination is very different. It all goes back to the importance of the ingredients.

There is food everywhere at McCrady’s

Including this rooftop garden

Brock refers to a book from the mid 1800’s, A Philosophy of Taste, that is a cookbook of plants for farmers and cooks. There are 26 varieties of cabbage listed in that book. How many do we see at the grocery store today? Maybe three or four? “We have lost the plants and characteristics of our foods”.

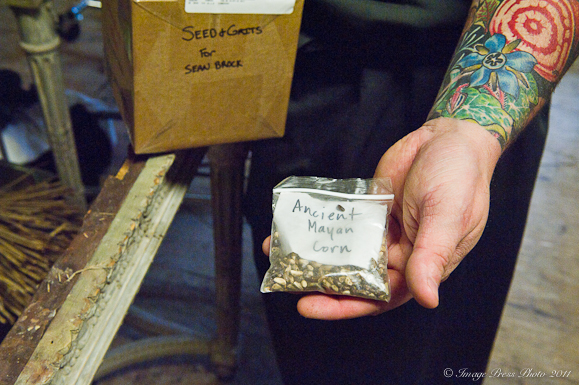

Chef Brock with his heirloom seed collection

Chef Brock has been working with Glenn Roberts and Dr. David Shields of Anson Mills for several years to grow and preserve heirloom seeds. He said that this work would not be possible without the help of Clemson University’s Dr. David Bradshaw. He showed us his heirloom seed collection with some varieties preserved from hundreds of years ago. There is even a Global Seed Vault in the Arctic, created to store these heirloom treasures, now with over 500,000 varieties preserved.

This is quite the find

Charleston’s Lowcountry cuisine is a product of its location and availability of foods that were grown at the time based on crop rotation (plants like corn, peas, rice, benne and okra are traditional ingredients). You harvested what animals were around you (wild boar, alligator and rabbits) and fresh seafood. The cuisine of Charleston has had its own voice and style since the late 1600’s with influences from Italy, Africa and France. Brock and many of the Charleston chefs are working hard to recreate this style of cooking with authentic local ingredients and heirloom produce.

Chef Brock’s tattoos represent his heirloom seed projects

If you had asked Brock five years ago what he would be doing now, he said that it certainly would not be this. Molecular gastronomy and the use of nitrogen in cooking played a large part in his cooking early on (and still does to some extent today). Now this Chef is reaching back in history to create authentic dishes using heritage ingredients. In fact, he is hoping to pick up wherever Glenn Roberts leaves off and wants to devote his life preserving heritage products at some point in the future.

We headed over to Husk for a late lunch

This work does not end with heirloom plants. He is also passionate about changing the way we treat our animals that become food on our table and is sourcing heritage breeds of livestock for his restaurants. Brock has raised his own herd of pigs (treating them to chocolate and Fruit Loops from time to time). He had a sleepless evening the night before they were dropped off for harvesting. However, it was an incredibly proud moment to share them with his culinary team and ultimately, the guests at his restaurant.

In front of the kitchen at Husk

The poultry industry is of particular concern to this chef. It is appalling the way these animals are raised and treated. “Every time you buy food, you cast a vote. Here is my money, thank you so much for treating the chickens that way. Keep on doing what you are doing.” He said no one ever wants to see the videos about how the animals are raised and harvested, yet continue to eat certain products and brands. “We have to fix it. We have to stop talking and just do it”.

Brock wants to bring properly raised heritage breeds of poultry back into the kitchens. “If the chefs cook it and taste the difference and write about it, it can change the industry. We may pay more, but we have to say that is what I need to be cooking”.

I had to try the smoked chicken after getting a whiff of this!

When asked why Charleston has so many great chefs and restaurants, Brock says “The circle is finally complete here”. There are many elements of this circle. The local people in Charleston are incredibly supportive and are open to anything he serves. Dishes that might not be welcomed in some cities are supported by the patrons in Charleston which gives the chef the opportunity to experiment. This was true in the 1600’s when rice first came to Charleston, and is true today. The city has grown up on great food, generation after generation.

“The chefs are now cooking with the proper ingredients with unique inspiration based on our history. People are coming here to experience it. If it tastes better, you will want more. It’s best for the environment, the economy and it’s just right.”

Charcuterie plate at Husk. Everything is made in-house.

Rabbit Rillettes with Green Goddess Dressing

If you dine at Husk or McCrady’s, you will eat vegetables that are just hours out of the ground, enjoy buttermilk benne seed rolls, savor housemade charcuterie and have a smoked heritage breed chicken with homemade barbecue sauce. You will then understand the passion Chef Brock has for bringing our foods back the way they should be and the way they were meant to be enjoyed. There is nothing better tasting than real food.

Thank you so much to Chef Brock for his time and graciousness during our visit. It was a truly inspiring and empowering experience.

Sea Island Red Peas

Chef Brock shared his recipe for Hoppin’ John with me. I ordered the authentic ingredients (Carolina Gold Rice and Sea Island Red Peas) from Anson Mills. (You can order them here.) I am a total convert after making this recipe. It is nothing like the rice and beans that we normally have once a year (New Year’s Day). This dish had incredible flavors because the focus was on good ingredients. It is a simple dish, easy to prepare and should be served on a regular basis. It is that good.

This ain’t your Momma’s Hoppin’ John!

We liked it best served as a stew with lots of broth in the bowl.

I could eat this as a meal by itself

We at Bunkycooks ask that you support your local farmers and bring the best to your table. Know where your food comes from.

Enjoy!

You might like to read another interview of Chef Brock by Joyce at Friends Drift Inn.

Hoppin' John

Ingredients:

For the red peas:

1 cup Anson Mills Sea Island Red Peas, soaked in water and refrigerated overnight, drained

2 quarts stock (preferably pork, but chicken will do)

1 large onion, medium dice

1 large carrot medium dice

2 celery stalks, medium dice

2 garlic cloves, peeled and sliced thin

1 bay leaf

For the rice:

1 cup Anson Mills Carolina Gold Rice

Salt and Cayenne pepper to taste

7 Cups Water

4 Tablespoons Butter

Directions:

For the red peas:

In a large stockpot, bring the stock to a simmer and add all ingredients. Cook for 1 hour over low heat, partially covered. When peas are tender, season with salt.

For the rice:

Bring the water and salt to a boil in a heavy-bottomed stock pot. Add the rice, stir once, and return to a simmer. Simmer gently, uncovered, stirring occasionally, until the rice is almost fully cooked, about 15 minutes (do not overcook). Drain the rice and rinse with cold water.

Preheat the oven to 300 degrees. Spread the rice onto a sheet tray. Place it in the oven to dry, stirring occasionally (mine took about 10 minutes). Be careful not to smash the rice. Dice the butter and spread evenly over the rice. Continue stirring every few minutes until the butter has melted.

Recipe Courtesy of Executive Chef Sean Brock – McCrady’s and Husk

Charleston, South Carolina