Indigenous Foods of the Southwest – Original Native American Cuisine

“We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, and the winding streams with tangled growth, as ‘wild’. Only to the white man was nature a ‘wilderness’ and only to him was the land ‘infested’ with ‘wild’ animals and ‘savage’ people. To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with blessings of the Great Mystery.” ~ Chief Luther Standing Bear of the Oglala band of Sioux

It seems that when we talk about the history of food in the United States we often look to Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, and Asia for the ingredients and techniques that are used extensively in our cuisine. On my recent travels to Southern Arizona I wanted to rediscover the foods of the original settlers, the Native Americans, to understand how these people survived and how their heirloom ingredients are used today.

I expected to find numerous sources and places to experience our country’s original indigenous foods, considering we were in the Southwest and in the Sonoran Desert where many Native American tribes have existed for thousands of years. Instead, what I found is the lack of this type of cuisine. Few people still forage wild ingredients or cultivate and harvest native heirloom ingredients and that even fewer people and chefs use these ingredients in their kitchens today. Up until recently there has been a genuine lack of interest in preserving the cuisine of the Native American culture.

When we speak of Native American food, many people think of pinto beans and fry bread, however as I learned, these are not the original traditional foods of the Native Americans. While the Fry Bread House in Phoenix, Arizona has been honored for its preservation of traditional foods, fry bread was a product of the rations the Native Americans were given by the U.S. government when they were displaced from their ancestral lands and moved to reservations in the late 1800s.

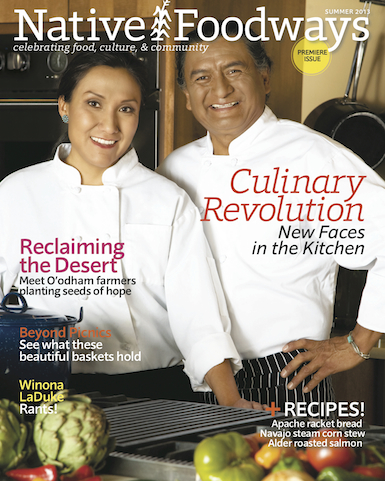

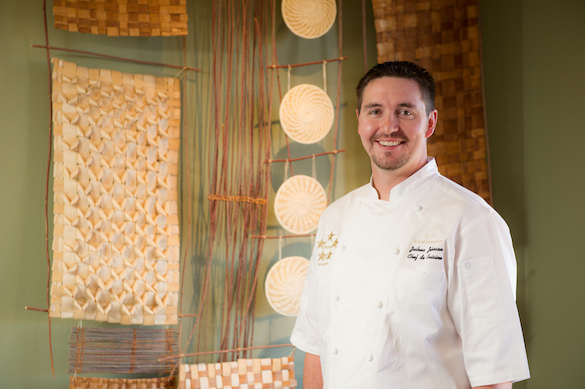

The recent revival of Native American foodways is largely due to several communities, committed individuals, and chefs. We spoke to several of the people leading this effort, including food writer Mary Paganelli Votto (TOCA, Native Foodways magazine, and Desert Rain Café) of Tucson, Chef Janos Wilder (James Beard Award winner, consultant and original chef of Kai and chef/owner of Downtown Kitchen & Cocktails) of Tucson, and Chef Joshua Johnson of Kai in Chandler, Arizona, to better understand the culinary roots of the Native Americans from the Southwest and the efforts to recapture the ingredients of the past.

The sobering history of Native Americans in this country has been documented in books and in movies and is imbedded in the memory of the tribes that once flourished in this country. While most groups of people have a real connection to their heritage foods and ingredients, such as the Italians, French, Africans, Asians, Latins and other immigrants who came to this country, the indigenous Native American tribes have very few of these traditions and relationships with their food because so much was taken from them. The Native Americans originally foraged for their seasonal food, preserved it, and farmed little. They depended on the natural bounty of the land for their existence. These foods nourished their bodies and also had medicinal and health benefits.

As the Native Americans were taken from their lands, they were given products by the U.S. government for their subsistence. This included white flour, white sugar, powdered milk, and lard. These were products they had never before used in their cooking, but could be preserved and transported easily and cheaply. They began to eat very differently and lost their native culture and food heritage. Due to this extreme change in diet, many Native Americans have become overweight and now have the highest rate of adult diabetes in the world.

Food writer, Mary Paganelli Votto moved to Tucson, Arizona from New York 15 years ago. Following the move to the Southwest, she became interested in learning more about Native American foodways. Despite finding little information about this topic, she pressed on. This pursuit began a personal journey to work with local communities and their elders to reinvigorate and reintroduce traditional Native American foods to the communities.

The Tohono O’odham Nation (formerly known as Papago Nation) is a Native American community located in the Sonoran Desert, about sixty miles west of Tucson. The size of Connecticut, it is home to about 28,000 people, with some of its original lands extending into Mexico. Mary has played an integral role collaborating with TOCA (Tohono O’odham Community Action) within the community to revive Native American foodways and traditions. Over a seven year period Mary worked with one of the elders, Frances Manuel, to co-author the cookbook, From I’Itoi’s Garden, which highlights the foods of the Sonoran desert and the traditions around these ingredients. TOCA is also teaching its members about self-sufficiency, farming practices, and focusing on cultural programs to revitalize and preserve the Tohono O’odham culture. In addition, Mary was instrumental in opening Desert Rain Café, a project of TOCA. This restaurant serves traditional and healthy Native American cuisine to the community and other customers.

Working with the elders to learn about the traditional native and wild foods has been the best way to discover and preserve this knowledge to pass on to the younger generations. Their combined information extends back over 150 years. Many of the original foods, Mary told us, such as the Tepary bean, were wild, but are now cultivated. A staple of the Tohono O’odham people (and other Native American communities), they are grown in two varieties, a brown and white bean, which are very different in flavor and texture. High in protein, fiber, and nutrients, this is a primary source of food for the community. When traditional ingredients such as Tepary beans or Cholla buds (harvested from the Cholla cactus) were the only foods that were consumed, there was never a problem with diabetes amongst Native Americans.

“The indigenous foods of the Sonoran Desert have a very low glycemic index,” Mary told us. “Cholla buds are high in calcium and since there were no goats or cows for milk (which the Spanish brought over), these wild foods provided important dietary supplements naturally. They were wild and hand harvested and due to their stickiness (with a consistency much like okra), they coat the stomach and prevent the blood sugar levels from going up.”

“The indigenous people were also very active. There’s a lot of movement when you harvest wild foods. The Saguaro cactus harvest takes place during the hot summer season. Fifteen-foot poles made from the ribs of the cactus are used to harvest the fruit, one piece at a time. The level of exercise contributed to the health of the tribes.” She went on to say, “Much of this history has been forgotten and now many people think of fry bread as a traditional Native American food. This is not indigenous for any Native American community and was developed out of people being given commodity food including white flour, powdered milk, and oil.”

Mary told us, “There’s a lot of misinformation and misconceptions out there. In reality, there are a lot of wonderful things happening. We are revitalizing the foods and wellness efforts and sharing what the true and indigenous foods really are. Each community has its own truly indigenous foods that are unique to them. It’s just like Italy; it’s very regional. Each region has different ingredients and preparations.”

Since we could not travel to Desert Rain Café, Mary brought some of the traditional dishes to us along with a bag of their hand harvested ingredients: brown and white Tepary beans; Saguaro syrup (Bahidaj Sitol); Chiltepin peppers; Cholla buds; and Saguaro seeds. With limited quantities of the products available due to the ingredients being primarily wild, the labor intensive process it takes to harvest them, combined with the amount of raw ingredients that it takes to make the product (such as the Saguaro syrup), the prices of these ingredients were quite expensive. However, the dishes we tasted were very flavorful with basic and simple preparation.

“The Tohono O’odham people ate very simple foods created with just water, the product, and spice from the Chiltepins. There was sea salt gathered from Mexico, but not many herbs, “ Mary told us. “It was basic, slow cooked food. Sometimes there were meat bones or perhaps wild garlic or onions (we’re not sure if they were indigenous or not). They did eat rabbit or deer. They would also grind up Saguaro or Cholla as an additional nutrient or thickener. They knew it would add flavor and nutrition. There were so many things that were edible. Cooking in ash, using traditional wood, has been found to add important minerals.”

With the high cost of these basic ingredients, we knew there would not be a huge revival to the Native American foodways movement much beyond the community. “These ingredients are hand harvested. You can’t just start a Cholla bud farm and the Saguaro cactus have to be at least 70 years old before they grow an arm and that’s where the fruit comes from. Some things are just meant to be in small quantities.”

Small quantities and limited ingredients, yet a Native American restaurant is the only AAA Five Diamond and Forbes Five Star awarded restaurant in the state of Arizona and one of the best places to dine in The United States. We traveled to Chandler, Arizona to visit and dine at Kai to learn more about an award-winning chef’s philosophy when preparing indigenous Native American cuisine at this renowned restaurant at the Sheraton Wild Horse Pass Resort.

Sous Vide Roots, Asparagus, & Exotic Mushrooms in their Soil. This dish takes the chef eight minutes to assemble.

Kai (the word for “seed” in the Pima language), focuses on the foods and traditions of the Pima and Maricopa tribes. Located in the Gila River Community (just a short drive from Phoenix), Chef de Cuisine Joshua Johnson, sources locally farmed ingredients from several Native American farmers, including their own Gila River Indian Community. With world-class service and extraordinary culinary talent, Kai takes many of the traditional Native American foods and combines them with global influences to create stunning pieces of art on the plate and for the palate. These beautiful dishes pay homage to the traditions of the tribes which have inspired the restaurant and it’s menu.

Working with as many as thirty to forty elders over his seven years at Kai, Chef Joshua has a deep respect for the Native American culture and foods. “I’m trying to make great food every day at Kai. The Native American people are very proud, so creating a full menu with limited ingredients and a limited source for those ingredients is a challenge. With these products, I want old ways honored and I want people to think twice about how the original tribes did this and to pay respect to the way things were done in the past.”

“There aren’t a lot of ingredients to source and at a Five Star, Five Diamond restaurant. I can’t have Cholla buds in five dishes. I maximize what I get from Native American and local farmers. I am using not only local ingredients, but I’m sourcing from local Native American farmers and producers,” he told us. “One dish on the new menu is dedicated entirely to Ramona Farms, who I’ve been working very closely with. She has been a farmer for almost forty years in this valley. I am using her Tepary beans, black eyed peas, and Giza, which is a smoked cracked corn. It’s truly amazing. It sits for sixty days releasing the milk and then is roasted over Mesquite overnight until it’s dry.”

Chef Joshua shared, “The Native American people were oppressed for over 100 years. So many ingredients were forced upon them while other people were able to farm and source their own unique foods. With a whole culture that was suppressed for so long, at Kai we want to celebrate the Native American foods and people like Ramona at Ramona Farms. It’s about the community that supports us; without them we’d be just another restaurant at the Sheraton Horse Pass.”

With the high cost of some of these ingredients, a high-end restaurant can afford to use them, but they’re not as likely to be on the menus of most other local restaurants. Chef Joshua explained, “Cholla buds only open one time a year, after the first good rain. That’s when they need be harvested. The same with the Saguaro cactus.” He agreed with what Mary Paganelli Votto had said in a prior interview, “It’s very labor intensive in the dead of summer and it takes a lot of acres of Saguaro fruit to make a few ounces of syrup. We’re not likely to see mom and pop shops using these ingredients.” And some of these unique ingredients, such as Cholla buds, are very different and not always widely accepted.

In describing my reaction to the Cholla bud to Chef Joshua, I referred to them as having a bit of a slimy texture, much like okra and he replied, “You say that about them and you are trying to seek these foods out. When I put them on the everyday person’s plate, if it’s not a French fry or it’s not been prepared on some cooking show by some awesome chef, then they are afraid to try them. The more we use them, the more they’re left on the plate. We’re not pushing and selling these foods like a cheeseburger from McDonalds. We don’t respect these foods enough to educate people about them.”

Grilled Tenderloin of Tribal Buffalo with Smoked Corn Puree, Cholla Buds, Merquez Sausage, Scarlet Runner Bean Chili, and Saguaro Blossom Syrup

He went on, “If you or I were to talk about the foods we grew up with, we would probably have thirty to forty things we could name. When I speak with the elders, they have very few foods they relate to and talk about everything being put on fry bread or they talk about Giza, the corn I mentioned earlier. It’s a joke with the Giza. They said it’s like crack cocaine. It’s so good and so rare. We can only get it once a year. Or coffee. Coffee was something rare for them, too.”

One of the latest projects for Chef Joshua is his work with the Navajo-Churro Sheep Breeders Association in Flagstaff, Arizona. “The Navajo-Churro sheep have mostly been used for their fur in the past. They are very small, 75 pounds at most and prehistoric in appearance with their horns. They date back 150 years and are very durable, resistant to the extreme temperatures and are resistant to diseases. They are versatile and never went anywhere. They were popular back then, but forgotten. It’s taken me years to line up enough breeders to be able to put this lamb on the menu.” It seems that the sheep were not the only source of food that was forgotten for so many years.

When thinking back on what I had learned from our time in Arizona researching Native American foodways, indigenous ingredients, and the food culture of the local tribes, these words from my follow-up discussion with Chef Joshua summed it up best. “The Pima and Maricopa Indians had what was called the ‘Walking Season.’ Nature gave them their ingredients and they took them, dried them, and lived off of them for the next year. They went foraging with packs of Chia seeds to sustain them since these seeds gave them the nutrition they needed to go walking for days to harvest the ingredients. They were truly a remarkable and amazing people before the English and European settlers came. They were far ahead of their time, far more than we could ever process.”

While many things have been forgotten, there is a committed revival in the Southwest of the Native Americans and their food and culture. Younger people are interested in learning about their heritage and there are chefs who are beginning to focus on the traditional Native American foodways. While many people think of Native American cuisine as being more closely related to Mexican food, as we learned, it is not. If you lose the foods, you lose the people. Thankfully, the more we educate ourselves and get involved, the more we can prevent history from repeating itself.

I prepared a White Tepary Bean Stew based on the recipe from Desert Rain Café. While it was incredibly basic (beans, water, salt, and short ribs), I was impressed at the flavors that developed over hours of slow cooking. We added just a bit of hot pepper sauce when it was served (I could have added a Chiltepin pepper while it cooked). This was all it needed to give it a little more complexity. This proved that really tasty food can be created with just a few simple ingredients.

For more information about Native American foodways, here are some links you might be interested in. You can also purchase most of the ingredients mentioned in this article through TOCA’s website.

TOCA (Tohono O’odham Community Action)

From I’itoi’s Garden – by Mary Paganelli and Frances Manuel

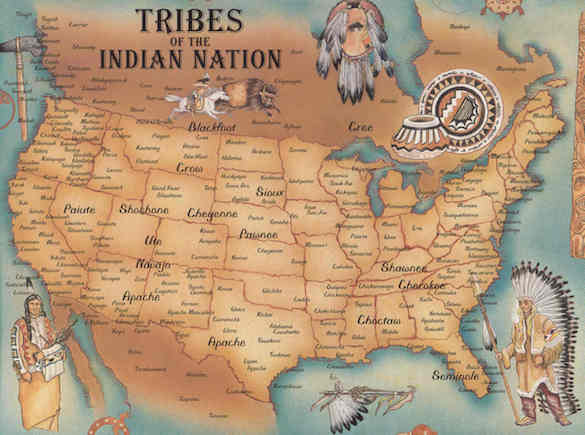

Note – Top photo of the map is from the Internet

* Photos courtesy of Kai and the Sheraton Wild Horse Pass Resort

** Photo courtesy of The Navajo-Churro Sheep Association

This content is protected under International Copyright Laws. Bunkycooks provides this content to its readers for their personal use. No part (text or images) may be copied or reproduced, in whole or in part, without the express written permission of bunkycooks.com. All rights reserved.

Traditional O'odham White Tepary Stew

After cooking the beans and meat together, I removed the lid and let the additional water boil down over a medium heat for about an hour. As the water reduced, the stew became thick and almost creamy, which was the texture of the stew we had from Desert Rain Cafe.

Ingredients:

1 cup of dried white Tepary beans, rinsed and picked through

10 cups water

1 teaspoon salt

1 pound oxtails, beef short ribs, deer or rabbit

Directions:

Place beans, water and 1 teaspoon of salt in a stockpot. Bring to a boil, reduce heat and simmer, covered, for one and a half hours. Add meat to the bean mixture, cover, and cook for one more hour (I cooked mine an additional hour), under beans are tender and meat is falling off the bone.

* This recipe is also perfect for cooking in a crockpot or slow cooker. Place all of the ingredients in the slow cooker and cook on medium or high for about 8 hours.

Recipe courtesy of Frances Manuel, San Pedro Village